Can the Uk Become a Absolute Monacary Again

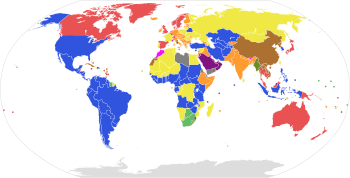

1 This map was compiled according to the Wikipedia list of countries by system of regime. See there for sources.

2 Several states constitutionally deemed to exist multiparty republics are broadly described by outsiders every bit disciplinarian states. This map presents only the de jure form of regime, and not the de facto degree of democracy.

Accented monarchy [one] [2] (or Authoritarianism as a doctrine) is a class of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right. In this kind of monarchy, the king is sometimes express past a constitution (since modern times). Withal, in some absolute monarchies, the king is by no means limited and has accented ability.[three] These are oftentimes hereditary monarchies. On the other manus, in constitutional monarchies, in which the dominance of the caput of country is also bound or restricted past the constitution, a legislator or unwritten customs, the male monarch is non the only one to decide, and his entourage also exercises power, mainly the prime number minister.[3]

Absolute monarchy in Europe declined substantially following the French Revolution and World State of war I, both of which led to the popularization of theories of regime based on the notion of popular sovereignty.

Absolute monarchies include Brunei, Eswatini, Oman, Saudi arabia, The holy see and the individual emirates composing the United Arab Emirates, which itself is a federation of such monarchies – a federal monarchy.[iv] [v] [half-dozen] [7] [8] [9] [10]

Historical examples of accented monarchies [edit]

Outside Europe [edit]

In the Ottoman Empire, the Sultan wielded absolute ability over the state and was considered a Padishah meaning "Cracking King" by his people. Many sultans wielded absolute ability through heavenly mandates reflected in their title, such equally "Shadow of God on Globe". In ancient Mesopotamia, many rulers of Assyria, Babylonia and Sumer were absolute monarchs likewise. In ancient and medieval India, rulers of the Maratha, Maurya, Satavahana, Gupta, Chola, Mughal, and Chalukya Empires, too equally other major and small empires, were considered accented.

Throughout Imperial Prc, many emperors and one empress (Wu Zetian) wielded accented ability through the Mandate of Sky. In pre-Columbian America, the Inca Empire was ruled by a Sapa Inca, who was considered the son of Inti, the sun god and accented ruler over the people and nation. Korea nether the Joseon dynasty and short-lived empire was also an absolute monarchy, though the Kim dynasty in Democratic people's republic of korea functions equally a de facto monarchy.[11]

Europe [edit]

Throughout much of European history, the divine right of kings was the theological justification for accented monarchy. Many European monarchs claimed supreme autocratic power by divine right, and that their subjects had no rights to limit their power. James Six and I and his son Charles I tried to import this principle into Scotland and England. Charles I'south attempt to enforce episcopal polity on the Church of Scotland led to rebellion by the Covenanters and the Bishops' Wars, then fears that Charles I was attempting to institute absolutist authorities forth European lines was a major cause of the English Civil War, despite the fact that he did rule this manner for 11 years starting in 1629, after dissolving the Parliament of England for a time. The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples [12] or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in European history. By the 19th century, divine correct was regarded equally an obsolete theory in most countries in the Western world, except in Russian federation where information technology was notwithstanding given acceptance every bit the official justification for the Tsar'southward power until February Revolution in 1917 and in the Vatican City where information technology remains today.

Denmark–Norway [edit]

Absolutism was underpinned by a written constitution for the offset time in Europe in 1665 Kongeloven , 'King'south Constabulary' of Denmark–Norway, which ordered that the Monarch

shall from this day forth be revered and considered the well-nigh perfect and supreme person on the Earth by all his subjects, standing higher up all human laws and having no judge to a higher place his person, neither in spiritual nor temporal matters, except God lone.[13] [14]

This law consequently authorized the king to cancel all other centers of power. Most of import was the abolition of the Council of the Realm in Denmark. Absolute monarchy lasted until 1814 in Norway, and 1848 in Denmark.

Habsburgs [edit]

| | This section needs expansion. Yous can assist by adding to it. (August 2021) |

Hungary [edit]

| | This section needs expansion. Y'all can help by adding to it. (August 2021) |

France [edit]

Louis XIV of French republic (1638–1715) is ofttimes said to have proclaimed Fifty'état, c'est moi! , 'I am the Land!'.[15] Although often criticized for his extravagances, such as the Palace of Versailles, he reigned over France for a long period, and some historians consider him a successful absolute monarch. More recently, revisionist historians[ who? ] have questioned whether Louis' reign should be considered 'absolute',[ example needed ] given the reality of the balance of power betwixt the monarch and the nobility, also equally parliaments.[16] [ need quotation to verify ] One theory is that that he congenital the opulent palace of Versailles and merely gave preferment to nobles who lived near it to get together nobility in Paris and to concentrate power equally a centralized regime. This policy also had the effect of separating nobles from their feudal armies.

The Rex of France concentrated legislative, executive, and judicial powers in his person. He was the supreme judicial authority. He could condemn people to death without the right of appeal. It was both his duty to punish offenses and stop them from beingness committed. From his judicial dominance followed his power both to brand laws and to annul them.[17]

Prussia [edit]

In Brandenburg-Prussia, the concept of absolute monarch took a notable turn from the above with its accent on the monarch as the "start servant of the state", but it also echoed many of the important characteristics of authoritarianism. Frederick William (r. 1640–1688), known every bit the Keen Elector, used the uncertainties of the last stages of the Thirty Years' War[ citation needed ] to consolidate his territories into the dominant kingdom in northern Federal republic of germany, whilst increasing his power over his subjects. His actions largely originated the militaristic streak of the Hohenzollerns.

Frederick William enjoyed support from the nobles, who enabled the Great Elector to undermine the Diet of Brandenburg and other representative assemblies. The leading families saw their time to come in cooperation with the central government and worked to establish absolutist ability.

The most significant indicator of the nobles' success was the institution of two tax rates – one for the cities and the other for the countryside – to the bully reward of the latter, which the nobles ruled. The nobles served in the upper levels of the elector's regular army and bureaucracy, but they also won new prosperity for themselves. The back up of the Elector enabled the imposition of serfdom and the consolidation of land holdings into vast estates which provided for their wealth.

They became known equally Junkers (from the German language for young lord, junger Herr). Frederick William faced resistance from representative assemblies and long-independent cities in his realm. City leaders frequently revolted at the imposition of Electorate authority. The concluding notable attempt was the uprising of the city of Königsberg which allied with the Estates General of Prussia to refuse to pay taxes. Frederick William crushed this revolt in 1662, by marching into the city with thousands of troops. A similar arroyo was used with the towns of Cleves.[18]

Russia [edit]

Until 1905, the Tsars and Emperors of Russia governed equally absolute monarchs. Ivan the Terrible was known for his reign of terror through oprichnina. Peter I the Great reduced the ability of the Russian nobility and strengthened the key power of the monarch, establishing a hierarchy and a police force state. This tradition of absolutism, known equally Tsarist autocracy, was expanded by Catherine Ii the Great and her descendants. Although Alexander Ii made some reforms and established an independent judicial system, Russia did not accept a representative associates or a constitution until the 1905 Revolution. All the same, the concept of absolutism was so ingrained in Russia that the Russian Constitution of 1906 still described the monarch equally an despot. Russia became the terminal European land (excluding Vatican Urban center) to abolish absolutism, and it was the only i to do so as late as the 20th century (the Ottoman Empire drafted its start constitution in 1876).

Sweden [edit]

The form of government instituted in Sweden under King Charles Xi and passed on to his son, Charles XII is commonly referred to as absolute monarchy; however, the Swedish monarch was never absolute in the sense that he wielded capricious ability. The monarch withal ruled under the constabulary and could but legislate in agreement with the Riksdag of the Estates; rather, the absolutism introduced was the monarch'south power to run the regime unfettered past the privy council, reverse to before practise. The absolute rule of Charles XI was instituted by the crown and the Riksdag in order to acquit out the Slap-up Reduction which would have been made impossible by the privy council which comprised the loftier nobility.

Later the death of Charles XII in 1718, the system of absolute rule was largely blamed for the ruination of the realm in the Smashing Northern War, and the reaction tipped the residuum of ability to the other extreme cease of the spectrum, ushering in the Age of Liberty. After half a century of largely unrestricted parliamentary rule proved just as ruinous, King Gustav 3 seized dorsum imperial power in the coup d'état of 1772, and later once again abolished the privy quango under the Union and Security Act in 1789, which, in turn, was rendered void in 1809 when Gustav Four Adolf was deposed in a coup and the constitution of 1809 was put in its place. The years betwixt 1789 and 1809, then, are likewise referred to every bit a period of accented monarchy.

Contemporary trends [edit]

Many nations formerly with absolute monarchies, such every bit Jordan, Kuwait and Morocco, have moved towards constitutional monarchy. However, in these cases the monarch still retains tremendous power, even to the extent that by some measures, parliament's influence on political life is viewed equally negligible.[xix] [20] [21] [ commendation needed ]

In Bhutan, the government moved from absolute monarchy to constitutional monarchy post-obit planned parliamentary elections to the Tshogdu in 2003, and the ballot of a National Assembly in 2008.

Nepal had several swings between constitutional rule and direct dominion related to the Nepalese Civil War, the Maoist insurgency, and the 2001 Nepalese royal massacre, with the Nepalese monarchy being abolished on 28 May 2008.[22]

In Tonga, the King had majority control of the Legislative Assembly until 2010.

Liechtenstein has moved towards expanding the power of the monarch: the Prince of Principality of liechtenstein was given expanded powers subsequently a referendum amending the Constitution of Liechtenstein in 2003, which led the BBC to describe the prince as an "absolute monarch over again".[23]

Electric current absolute monarchies [edit]

Kingdom of saudi arabia [edit]

Saudi Arabia is an absolute monarchy, and according to the Basic Police of Saudi Arabia adopted by Purple Prescript in 1992, the King must comply with Shari'a (Islamic constabulary) and the Qur'an.[6] The Qur'an and the body of the Sunnah (traditions of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad) are declared to be the Kingdom'southward Constitution, only no written modern constitution has always been promulgated for Saudi arabia, which remains the just Arab nation where no national elections have e'er taken place since its founding.[30] [31] No political parties or national elections are permitted and co-ordinate to The Economist's 2010 Democracy Alphabetize, the Saudi authorities is the eighth most authoritarian authorities from among the 167 countries rated.[32] [6]

Scholarship [edit]

At that place is a considerable diverseness of stance by historians on the extent of absolutism amid European monarchs. Some, such as Perry Anderson, argue that quite a few monarchs accomplished levels of absolutist control over their states, while historians such as Roger Mettam dispute the very concept of absolutism.[33] In general, historians who disagree with the appellation of absolutism debate that nigh monarchs labeled as absolutist exerted no greater power over their subjects than any other non-absolutist rulers, and these historians tend to emphasize the differences between the absolutist rhetoric of monarchs and the realities of the effective use of ability by these accented monarchs. Renaissance historian William Bouwsma summed upwards this contradiction:

Nothing so clearly indicates the limits of regal ability equally the fact that governments were perennially in fiscal trouble, unable to tap the wealth of those ablest to pay, and likely to stir up a costly revolt whenever they attempted to develop an adequate income.[34]

—William Bouwsma

Anthropology, sociology, and ethology as well every bit diverse other disciplines such as political science attempt to explain the rise of absolute monarchy ranging from extrapolation more often than not, to sure Marxist explanations in terms of the class struggle as the underlying dynamic of human historical development generally and accented monarchy in detail.

In the 17th century, French legal theorist Jean Domat defended the concept of absolute monarchy in works such as "On Social Order and Absolute Monarchy", citing absolute monarchy as preserving natural order as God intended.[35] Other intellectual figures who have supported absolute monarchy include Thomas Hobbes and Charles Maurras.

See also [edit]

- Autocracy

- Authoritarianism

- Constitutional monarchy

- Criticism of monarchy

- Democracy

- Despotism

- Dictatorship

- Enlightened authoritarianism

- Jacques Bossuet

- Monarchomachs

- Theonomy

- Thomas Hobbes

- Totalitarianism

- Tyranny

References [edit]

- ^ Goldie, Mark; Wokler, Robert (2006-08-31). "Philosophical kingship and aware despotism". The Cambridge History of Eighteenth-Century Political Thought. Cambridge University Printing. p. 523. ISBN9780521374224 . Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ Leopardi, Giacomo (2013) [original 1898]. Zibaldone. Farrar Straus Giroux. p. 1438. ISBN978-0374296827.

- ^ a b Harris, Nathanial (2009). Systems of Government Monarchy. Evans Brothers. ISBN978-0-237-53932-0.

- ^ Stephens, Michael (2013-01-07). "Qatar: regional backwater to global role player". BBC News.

- ^ "Q&A: Elections to Oman'south Consultative Quango". BBC News. 2011-10-13.

- ^ a b c Cavendish, Marshall (2007). World and Its Peoples: the Arabian Peninsula. p. 78. ISBN978-0-7614-7571-2.

- ^ "Swaziland profile". BBC News. 2018-09-03.

- ^ "State Departments". Vaticanstate.va. Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2014-01-25 .

- ^ "Vatican to Emirates, monarchs keep the reins in modern earth". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2013-ten-16.

- ^ "Land Departments". www.vaticanstate.va. Archived from the original on 2020-04-11. Retrieved 2019-09-21 .

- ^ Choi, Sang-hun (27 October 2017). Interior Infinite and Furniture of Joseon Upper-course Houses. Ewha Womans Academy Printing. p. 16. ISBN9788973007202 – via Google Books.

Joseon was an absolute monarchy

- ^ Merriman, John, A History of Modernistic Europe: From the French Revolution to the Present, 1996, p. 715

- ^ "Kongeloven af 1665" (in Danish). Danske konger. Archived from the original on 2012-03-30.

- ^ A partial English translation of the law can be establish in Ernst Ekman, "The Danish Royal Law of 1665" pp. 102-107 in: The Periodical of Modernistic History, 1957, vol. ii.

- ^ "Louis Xiv". HISTORY . Retrieved 2018-10-05 .

- ^ Mettam, R. Ability and Faction in Louis XIV's French republic, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1988.

- ^ Mousnier, R. The Institutions of France nether the Absolute Monarchy, 1598-2012 V1. Chicago: The Academy of Chicago Press, 1979.

- ^ The Western Experience, Seventh Edition, Boston: McGraw-Hill, 1999.

- ^ Tusalem, Rollin F. (16 September 2021). "Bringing the Legislature Back In: Examining the Structural Effects of National Legislatures on Effective Democratic Governance". Regime and Opposition: 1–25. doi:ten.1017/gov.2021.32. ISSN 0017-257X. S2CID 240505261.

- ^ Tartter, Jean R. (1986). "Authorities and politics". In Nelson, Harold D. (ed.). Morocco, a country study. Area Handbook. Foreign Surface area Studies: The American Academy. pp. 246–247. OCLC 12749718.

Past 1985 the legislature appeared to have become more firmly established and recognized every bit a trunk in which notables representing accurate forces in the political spectrum could address national issues and problems. Only information technology had non gained real autonomy or a direct office in the shaping of government policies." [...] "In spite of its formally defined office in the code and monetary processes, the parliament had not established itself as an independent branch of government, attributable to the restrictions on its constitutional authority and the dominating influence of the king. The fact that the rex has been able to govern for long periods past zahir afterwards dissolving the legislative trunk has further underscored the marginality of the chamber.

- ^ Rafayah, Shakir (29 January 2022). "What role for political parties in Hashemite kingdom of jordan?". Arab Weekly . Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ Sharma, Gopal (2008-05-29). "Nepal abolishes centuries-old Hindu monarchy". Reuters . Retrieved 2020-12-01 .

- ^ "Liechtenstein prince wins powers". BBC News. 2003-03-16. Retrieved 2015-10-26 .

- ^ Authorities of Brunei. "Prime Minister". The Imperial Ark. Office of the Prime number Minister. Archived from the original on seven October 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ Sultan Qaboos Centre for Islamic Civilization. "About H.M the Sultan". Government of Oman, Diwan of the Purple Court. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ Nyrop, Richard F (2008). Area Handbook for the Persian Gulf States. Wildside Printing LLC. p. 341. ISBN978-i-4344-6210-7.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia's King Abdullah dies". BBC News. 23 January 2015. Retrieved 23 Jan 2015.

- ^ "Argentina's Jorge Mario Bergoglio elected Pope". BBC News . Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ Simelane, H.Southward. (2005), "Swaziland: Mswati 3, Reign of", in Shillington, Kevin (ed.), Encyclopedia of African history, vol. 3, Fitzroy Dearborn, pp. 1528–30, 9781579584559

- ^ Robbers, Gerhard (2007). Encyclopedia of world constitutions, Volume 1. p. 791. ISBN978-0-8160-6078-eight.

- ^ "Qatar elections to be held in 2013 - Emir". BBC News. November 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-01-06. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ The Economist Intelligence Unit. "The Economist Democracy Index 2010" (PDF). The Economist . Retrieved half-dozen June 2011.

- ^ Mettam, Roger. Power and Faction in Louis Xiv's French republic, 1991.

- ^ Bouwsma, William J., in Kimmel, Michael Southward. Absolutism and Its Discontents: State and Guild in Seventeenth-Century France and England. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1988, 15

- ^ "Jean Domat: On Defence force of Absolute Monarchy - Cornell College Student Symposium". 18 April 2009.

Farther reading [edit]

- Anderson, Perry. Lineages of the Absolutist State. London: Verso, 1974.

- Beloff, Max. The Historic period of Absolutism From 1660 to 1815 (1961)

- Blum, Jerome, et al. The European World (vol i 1970) pp 267–466

- ——. Lord and Peasant in Russia from the Ninth to the Nineteenth Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1951.

- Kimmel, Michael South. Absolutism and Its Discontents: Country and Society in Seventeenth-Century France and England. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1988.

- Méttam, Roger. Power and Faction in Louis XIV's French republic. New York: Blackwell Publishers, 1988.

- Miller, John (ed.). Authoritarianism in Seventeenth Century Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1990.

- Wilson, Peter H. Authoritarianism in Central Europe. New York: Routledge, 2000.

- Zmohra, Hillay. Monarchy, Aristocracy, and the State in Europe - 1300-1800. New York: Routledge, 2001

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Absolute_monarchy

0 Response to "Can the Uk Become a Absolute Monacary Again"

Post a Comment